Introduction

x7 (pronounced "except") is a stack-based pseudo-golfing language. While ostensibly a language meant to be used for golfing, it is more of a toy project to explore novel golfing ideas and it is not explicitly designed to minimize byte count. Instead, it aims for more of a middle ground that makes the language an accessible testing ground while still remaining terse and (hopefully) fun to golf and program in.

The language's main draw is its control flow based entirely on "raises", which work much like exceptions in Python or Java. The goal of this system is to allow a programmer to elide explicit checks and control edge cases more easily by structuring their code carefully.

This book provides documentation for the syntax and features of x7, as well as a list of all of its built-in instructions. Though informal, it is the language's primary specification and can serve both as a reference and as a gentle introduction.

Basic syntax

x7 is a stack-based language. If you've ever written Forth, used the dc calculator, or looked at any of the myriad stack-based esolangs before, you should feel right at home with this form of expressions.

There is a single stack of values onto which intermediate results are placed, and instructions pop arguments from it to manipulate before pushing the result.

Instructions used in this chapter

| Symbol | Name | Brief |

|---|---|---|

+ | add | Add two numbers. |

* | multiply | Multiply two numbers. |

T | times | Run a block a given number of times. |

e | except | Try to run a given block, falling back to a different one if it raises. |

r | raise | Raise. |

Intro

Here's a simple example. We compute 2*3+1 in RPN, leaving the number 7 on the stack.

1 2 3*+

> 7

Note the format of this example: the output after running the code is shown below it, with a > preceding it.

We will use this convention for all examples in the reference from this point onward. Examples may also be followed by pseudocode showing what it is equivalent to.

We learn some things about the language from this example. Each instruction is a single character long, so we can write * and + next to each other without ambiguity. However,

spaces are needed between decimal literals, because if they were written next to each other, it would be read as a single number. There is one exception to this: because

leading zeroes before decimals are not allowed, there is no ambiguity after a 0.

01 23

> 0 1 23

Variables

:x stores a value in a variable called x, while ;x retrieves it. Variable names can be any single character that is not a digit.

42:x 22:y ;x ;y ;x

> 42 22 42

This code would usually be written without spaces, as 42:x22:y;x;y;x. It has been formatted this way to make it easier to read.

Functions

By default, only the last line in a x7 file is executed. (It acts as an entry point, like main.) Other lines can be executed by using ; with the line number.

3 4

1 2;1

> 1 2 3 4

You can call any line (including the main line) any number of times, and they may recurse.

Blocks

Some instructions take blocks of source code. In the simplest case, this means reading the code in front of the instruction until reaching a backtick.

As an example, the T (times) instruction pops a natural number from the stack and runs a block that many times.

1 10T2*`

> 1024

In Ruby:

n = 1

10.times do

n *= 2

end

We push a 1 to the stack, then use T to double it 10 times, hence calculating \(2^{10} = 1024\).

Uses of T can nest as though T was an opening bracket and ` closed it:

1 4T2T2*``

> 256

n = 1

4.times do

2.times do

n *= 2

end

end

By doubling twice (multiplying by 4), 4 times, we get \((2^2)^4 = 4^4 = 256\) in a similar fashion to the previous example.

Auto-closing

Blocks close themselves at the end of a line, which is convenient for closing many at once:

0 10T10T10T1+

> 1000

n = 0

10.times do

10.times do

10.times do

n += 1

end

end

end

This power can be harnessed explicitly within a line by writing a closing brace.

0 10T10T1+}2*

> 200

n = 0

10.times do

10.times do

n += 1

end

end

n *= 2

Closing the T blocks early prevents the 2* from being placed inside them, so the result is 200 instead of 2535301200456458802993406410750.

} itself can also be capped with {:

0 2T{10T10T1+}2*

> 600

n = 0

2.times do

10.times do

10.times do

n += 1

end

end

n *= 2

end

Here we keep the 2* outside of the two inner 10T loops, but inside the 2T loop on the outside. { prevents } from being able to close blocks to the left of the {.

Multiple blocks

When an instruction takes more than one block, the syntax of all blocks other than the last one is different.

We need an example of an instruction that takes two blocks, so say hello to r (raise), which raises, and e (except), which acts like a try/catch.

e0}1

> 0

er}1

> 1

Here we see two examples where e is used. It tries to run the first block, but if and only if it raises, it runs the second block instead.

Note that the two blocks are separated with }. This is mandatory for instructions that take multiple blocks. The exact behaviour of this parsing can be seen here:

2Te2T0}1`2

> 0 0 2 0 0 2

stack = []

2.times do

begin

2.times do

stack.push(0)

rescue

stack.push(1)

end

stack.push(2)

end

The first } closes the second 2T (because it is inside the e) but not the first (because it is not inside the e), and is then consumed to begin parsing the second block.

The second block is closed by the `, followed (still inside a 2T) by the 2. As a result, the whole code executes twice, pushing two 0s, ignoring the 1 (because there is no raise)

and adding a 2.

Data types

This is a list of all of the base types for values in x7.

Instruction index

| Symbol | Name | Brief |

|---|---|---|

N | negate | Negate a number. |

D | divide | Divide two rationals. |

[ | list | Push an empty list. |

. | concat | Form two values into a list, add an element to a list from either end, or concatenate two lists. |

] | enlist | Enclose a value in a list. |

, | pair | Form a pair from two values. |

Numbers

All numbers are represented as fractions. They can be constructed with a combination of decimal literals and the instructions D (divide) and N (negate). They are displayed in a variety of forms by the interpreter:

1

> 1

1N

> -1

1 2D

> 0.5

1 3D

> 1.(3)

1 95D

> 0.0(105263157894736842)

52 58D

> 26/29

102 58D

> 1+22/29

102 58DN

> -1-22/29

Lists

Finite sequences of values. Built with [ (list), . (concat), and ] (enlist).

1 2.3.

> [1,2,3]

Although x7 is dynamically-typed, lists are homogenous. Two values can only be in a list together if they are compatible, meaning that one of the following holds:

- They are both rationals

- They are both pairs, and their respective elements are compatible

- They are both lists, and one or both of them is empty

- They are both non-empty lists, and the elements inside them are all compatible

Pairs

Two values. Together. Constructued with , (pair).

1 2,

> (1,2)

Stack manipulation

This chapter is a primer on how to use the language's facilities to shuffle values around on the stack.

Instructions used in this chapter

| Symbol | Name | Brief |

|---|---|---|

d | dup | Duplicate the top group on the stack. |

p | pop | Discard the top value on the stack. |

f | flip | Swap the top two groups on the stack. |

^ | yank | Duplicate the second group from the top of the stack. |

& | group | Concatenate the top two groups on the stack. |

_ | under | Run some code "under" the group on top of the stack. |

l | lift | Run separate blocks on the same arguments and push both the results. |

Basics

If you've used any stack-based language before, you'll be expecting these mainstays.

Duplicate a value (Forth's DUP):

1d

> 1 1

Get rid of one (Forth's DROP):

1p

>

Flip the top two (Forth's SWAP):

1 2f

> 2 1

Duplicate the second from the top (Forth's OVER):

1 2^

> 1 2 1

We're missing some common choices from Forth, which we'll address in the next section.

Temporary groups

It is sometimes convenient to use stack utilities on multiple values at once, treating them like a "group" of consecutive values.

This can be done with & (group), which joins values together into larger groups that can be as large as you want.

1 2& 1 2 3&&

> 1&2 1&2&3

When an instruction refers to "groups" instead of "values" in its documentation, it means it will treat these groups specially:

1 2&d

1&2 1&2

Any other instruction will simply dissolve the group entirely when it needs a value from it.

1 2 3&&4+

> 1 2 7

We can use this to replicate some other Forth words, like ROT:

1 2 3&f

> 2&3 1

Dipping

The last 2 tools included for the stack take blocks. The first is _ (under; often called dip in other languages),

which pops a group, executes the block, and pushes the popped group again. This lets you work lower on the stack, leaving higher values as they are.

1 2 3_+

> 3 3

We can finally emulate 2SWAP:

1 2 3 4&_&`f

> 3&4 1&2

Lifting

l (lift) takes two blocks, executes the second one, pops a group, rewinds to before it ran, runs the first block, then pushes the group that was popped from the first branch.

It sounds complicated, but all it really does is let you execute multiple functions on the same input and get both results:

3 3l+}*

> 6 9

Here we use it to compute both \(3 + 3 = 6\) and \(3 * 3 = 9\) without having to duplicate the inputs. This enables idioms reminiscent of a fork

in APL or Haskell's liftA2 function (when specialized to the (->) r functor), for which the instruction is named.

Raises

x7's namesake and one of its most standout features. Here's how to use them.

Instructions used in this chapter

| Symbol | Name | Brief |

|---|---|---|

r | raise | Raise. |

e | except | Try to run a given block, falling back to a different one if it raises. |

s | suppress | Ignore raises in a certain block. |

m | mask | Mask raises in a block, protecting them from one layer of being caught. |

! | invert | Logical NOT for raising. |

< | less than | Compare two values, expecting first < second. |

G | not less than | Compare two values, expecting first >= second. |

= | equal to | Compare two values, expecting first == second. |

/ | not equal to | Compare two values, expecting first != second. |

> | greater than | Compare two values, expecting first > second. |

L | not greater than | Compare two values, expecting first <= second. |

l | lift | Run separate blocks on the same arguments and push both the results. |

Intro

Raises happen all the time in x7 for all sorts of reasons. Some of them will be familiar from other languages, while others may seem strange because of x7's exclusive use of raises as control flow.

Here are some examples of cases that raise:

- Type errors, like trying to add a pair to a number

- Taking more values from the stack than it has

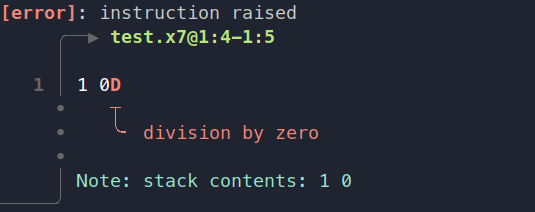

- Division by zero

- Reading an unassigned variable

- Explicitly raising with

r - Failed comparisons

When an instruction raises and it isn't caught by anything, a message is written to stderr explaining where the raise occurred and why it happened.

Rewinding

Catching raises works slightly differently to catching exceptions in other languages. See this example in Ruby:

x = 0

begin

x += 1

1 / 0

rescue

end

puts x

The output of this program is 1, because the x is incremented before the exception from dividing by zero is raised.

However, the analogous program in x7 acts differently:

0s1+1 0D

> 0

The s instruction suppresses exceptions just like our empty rescue block in Ruby does, so nothing is raised. But the value on the stack remained 0 without being incremented!

This is because almost every instruction in x7 that catches raises performs something called rewinding. If a block ends up raising, all the effects of that block are undone, making it as if it had never run at all.

The only exception is the ! (invert) instruction, which preserves any changes made when it catches a raise.

Handling

In this chapter, we will focus on the most fundamental ways to manipulate raises, but please note that these are not the only instructions that are aware of raises; as the language is designed around them, there are many instructions that treat them differently.

The e (except) instruction, seen already in chapter 2, implements a familiar "try/except" pattern. It takes two blocks and executes the first one, executing the second block if and only if the first one raises.

e1}2`e2 1 3 7r}2`

> 1 2

If the second block raises as well, it is not caught.

The s (suppress) instruction is like e without a second block. It simply catches all raises within it and ignores them.

s2r

> <empty>

The ! instruction catches raises as well, but it does not rewind:

!1r

> 1

If its block finishes without raising at all, ! raises.

!1 2 3`

> <raises>

Note that although ! does not itself rewind, its effects can still be rewound by other instructions outside it.

s!2r`r

> <empty>

Masking

x7 does not give different instructions different "types" of raise, so it may seem as though there is no way to tell them apart and that all raises can only be caught by the innermost handler.

For example, if we use s around a block to catch certain raises, how do we allow other raises to go through it to be affected by other handling instructions higher up?

This is the problem that masks solve. Masking an instruction makes it impossible to catch. Anything that would "catch" it simply removes the mask. Masks are created by the m instruction, which catches

any raise, adds one layer of masking to it, and reraises it. Here's an example:

smr

> <raises>

Normally, the raise from r would be caught by the s, but the mask "protects" it and allows it to go through. The effect wears off after one layer:

ssmr

> <empty>

However, you can also stack masks so they apply for more layers:

ssmmr

> <raises>

You can use different levels of masking to "pick" which handler the raise should be affected by.

eeemr}}}0`1`2

> 1

Conditions

x7 does not use booleans like most languages do. The only form of condition is "whether or not a certain block raises". As such, comparisons act like assertions:

1 2<

> <empty>

2 1<

> <raises>

The operators = (equal), / (not equal), < (less than), G (not less than), > (greater than), and L (not greater than)

simply check that their respective condititions hold for the top two values on the stack and raise if they don't.

For these so-called "conditional blocks", !, e, and l act like boolean NOT, boolean OR, and boolean AND respectively.

Additionally, s and e can be used to replicate if and if-else conditionals.